Part Two of Value-Delivery in the

Rise-and-Decline of General Electric

Illusions of Destiny Controlled & the World’s Real Losses

By Michael J. Lanning––Copyright © 2022 All Rights Reserved

This is Part Two of our four-part series on GE’s great rise and eventual dramatic decline, seen through our value-delivery lens. Businesses as much as ever need strategies that deliver superior value to customers, including via major product-innovation. Though now a faded star, GE’s lengthy history offers striking lessons on this fundamental challenge. Our two recent posts in this series provide an Introductory Overview and then Part One on GE’s first century. (Note from the author: special thanks to colleagues Helmut Meixner and Jim Tyrone for tremendously valuable help on this series.)

When Jack Welch became CEO in 1981, GE was already a leading global firm, with revenues of $27 billion, earnings of $1.6 billion, and market value of $14 billion. Led by Welch, GE then implemented an ingenious strategy that produced legendary profitable growth. By 2000, GE had revenues of $132 billion, earnings of $12.7 billion, and a market value of $596 billion, making it the world’s most valuable company. Yet, this triumphant GE strategy would ultimately prove unsustainable and self-destructive.

Not widely well understood, the Welch strategy was a distinct hybrid. It leveraged GE’s traditional, physical-product businesses––industrial and consumer––to rapidly expand its initially-small, financial-service businesses, thereby accelerating total-GE’s growth. At the same time, it grew those product-businesses slowly but with higher earnings for GE, by cutting costs––including reduced focus on product-innovation. Thus, for over two decades after 1980, this hybrid-strategy produced the corporation’s legendary, profitable growth.

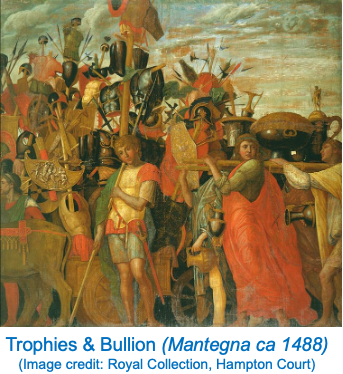

Welch did not fully explain this partially opaque and––given GE’s history––surprisingly financial-services oriented strategy. Instead, his preferred narrative was simpler and less controversial. It primarily credited GE’s great success to Welch’s cultural initiatives––not to the hybrid strategy––and emphasized total-GE growth more than that of the financial-businesses. Yet, the hybrid strategy and the crucial growth of the financia l-businesses were the real if partially obscured key to GE’s growth. The initiatives did improve GE’s culture but played little role in that growth. Still, fans embraced this popular, reassuring narrative about initiatives, helping make GE the most admired––not just most valuable––company. Like the ultimately unsustainable Roman triumphs of Caesar, much of the world would hail Welch’s GE success, without recognizing its longer-term flaws.

l-businesses were the real if partially obscured key to GE’s growth. The initiatives did improve GE’s culture but played little role in that growth. Still, fans embraced this popular, reassuring narrative about initiatives, helping make GE the most admired––not just most valuable––company. Like the ultimately unsustainable Roman triumphs of Caesar, much of the world would hail Welch’s GE success, without recognizing its longer-term flaws.

The Welch strategy seemed to triumph for over two decades, but eventually proved a tragic wrong turn by GE––and a misguided strategic model for much of the business world. In its first century, GE built huge, reliably profitable product-businesses, based on customer focused, science based, synergistic product-innovation. Now, its new hybrid of physical-product-and-financial businesses deemphasized much of this highly successful approach. For over twenty years after 1980, it leveraged GE’s product-business strengths to enable breath-taking growth of its financial-businesses––from $931 million in 1980 to over $66 billion in 2000––in turn driving total-GE’s spectacular, profitable growth.

However, this apparent, widely celebrated triumph was in fact a major long-term strategic blunder. It replaced GE’s great focus on product-innovation-driven growth with a focus on artificially engineered, financial-business growth. That hybrid-strategy triumph produced impressive profitable growth for two decades but was ultimately unsustainable. Its growth engine was inherently limited––unlikely to sustain major growth much beyond 2000––and self-destructive, entailing higher-than-understood risk. Most fundamentally, however it provided no adequate replacement for the historic, product-innovation heart of GE strategy.

Welch-successor Jeff Immelt and team recognized some of the limitations and risks of the hybrid strategy but lacked the courage and vision to fully replace it. In the 2008-09 financial crisis, the strategy’s underestimated risks nearly destroyed the company. GE survived, partially recovering by 2015, but having let product-innovation capabilities atrophy, GE was unprepared to create major new businesses. After 2015, lingering financial risks and new, strategic blunders would further sink GE, but its stunning decline traces most importantly to Welch’s clever yet long-term misguided, hybrid strategy.

GE’s 1981 crossroads––drift further or refocus on its electrical roots?

The GE that Jack Welch inherited in 1981 had always been a conglomerate––a multi-business enterprise. Yet, in GE’s first century it had avoided the strategic incoherence often associated with conglomerates––often unrelated businesses, assembled only on superficial financial and empire-building criteria. In contrast, though technologically diverse, most GE businesses pre-1981 shared important characteristics––mostly all manufacturing products with deep roots in electricity or electromagnetism. They thus benefited from mutually reinforcing, authentically synergistic relationships.

By the 1970s, however, GE had begun slightly drifting from those electrical roots, losing some synergy and coherence. GE plastics, originally developed for electrical insulation, evolved into large businesses mostly unrelated to electrical technology. More importantly, however, GE failed to persist in some key electrical markets. Falling behind IBM, GE exited computers in 1970. Despite software’s unmistakable importance, the company failed to develop major capabilities or business in this area. GE’s Solid State electronics division pursued semiconductors, but with limited success by the late 1970s. These markets were competitively challenging but also essential to digital technology, which has since come to dominate much of the world’s economy. New GE efforts in these markets might well have failed, but few firms had GE’s depth of capabilities, if it had possessed the will to succeed.

In 1980, GE businesses were dominantly electrical- and electromagnetic-related. 84% of revenues were: Power; Consumer (lighting and appliances); Medical Imaging; and Aircraft Engines––linked by turbine technology to Power. 13% were plastics and mining (a major 1976 acquisition). 3% were GE Credit Corp, financing customer purchases. Thus, GE faced a strategic crossroads as Welch took the helm––continue drifting from or redouble its historical focus on product innovation in its electrical roots.

To pursue the second option, Welch and team would have needed to deeply explore the evolving preferences and behaviors of customers in electrical markets, including digital ones neglected by GE. This team might have thus discovered new value propositions, deliverable via major product innovations, reinvigorating GE growth in its core markets.

Instead, Jack Welch led the company in a new strategic direction––further from its roots. It divested mining, but increasingly embraced non-electrically based businesses––expanding plastics and pursuing the glamourous yet strategically unrelated broadcasting-business, acquiring NBC in 1986.

in a new strategic direction––further from its roots. It divested mining, but increasingly embraced non-electrically based businesses––expanding plastics and pursuing the glamourous yet strategically unrelated broadcasting-business, acquiring NBC in 1986.

After the mid-1990s, moreover, GE widened its product-businesses’ focus––from primarily manufacturing-based, superior product-performance to include expanded industrial services. These proved more profitable and less reliant on product innovation.

Especially crucial, however, the new Welch strategy would also quietly but aggressively expand GE’s financial services. In his 2001 autobiography Jack: From the Gut (Warner Books), Welch recalls his first impressions of that initially unfamiliar business:

Of all the businesses I was given as a sector executive in 1977, none seemed more promising to me than GE Credit Corp. Like plastics, it was well out of the mainstream…and I sensed it was filled with growth potential… My gut told me that compared to the industrial operations I did know, this business seemed an easy way to make money. You didn’t have to invest heavily in R&D, build factories, and bend metal day after day. You didn’t have to build scale to be competitive. The business was all about intellectual capital—finding smart and creative people and then using GE’s strong balance sheet. This thing looked like a “gold mine” to me.

More difficult to execute than implied by this comment, the hybrid strategy nonetheless worked almost magically well, for two decades. GE Credit Corp (GECC)––later renamed and now termed here, in short, GEC––aggressively leveraged key strengths from GE’s traditional product-businesses. Thus, GEC would produce most total-GE growth in the Welch era, driving the company’s astounding market-value. Yet, with this hybrid strategy GE would eventually lose some of its strategic coherence, its businesses less related, while growth proved unsustainable much beyond 2000 and risk was higher-than-understood.

Meanwhile, GE’s ability to profitably deliver superior value––via customer focused, science based, synergistic product-innovation––had deteriorated. GE had taken a major wrong turn at its 1981 crossroads and would eventually find itself at a strategic dead-end.

Real cause of GE triumph––Welch-initiatives or the hybrid-strategy?

After 1981, Welch launched a series of company-wide cultural initiatives, broadly popular and emulated in the business community. These included the especially-widely adopted Six Sigma product-quality methodology. Another initiative mandated that each GE business must achieve a No. 1 or No. 2 market-share or close the business. Globalization pushed to make GE a fully global firm. Workout involved front-line employees to adopt Welch’s vision of a less bureaucratic culture. Boundaryless encouraged managers to freely share information and perspective across businesses. Services aimed to make service, like new equipment, a central element in GE product-businesses, investing in service technologies and rapidly expanding service revenues. E-business, by the late 1990s, encouraged enthusiastic engagement with e-commerce.

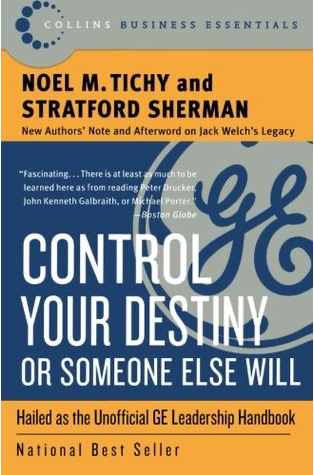

These initiatives likely helped make GE’s culture less bureaucratic, more decisive, and efficient. However, as GE business results soared, the initiatives were also increasingly credited––but unjustifiably––as a primary cause of those results. A leading popularizer of this misguided  narrative was Michigan business-professor Noel Tichy. His books hagiographically extolled the Welch approach. In the mid-1980s Tichy led and helped shape GE’s famous Crotonville management-education center, where GE managers were taught that the initiatives were key to GE’s success. Welch agreed, writing in Jack:

narrative was Michigan business-professor Noel Tichy. His books hagiographically extolled the Welch approach. In the mid-1980s Tichy led and helped shape GE’s famous Crotonville management-education center, where GE managers were taught that the initiatives were key to GE’s success. Welch agreed, writing in Jack:

In the 1990s, we pursued four major initiatives: Globalization, Services, Six Sigma, and E-Business… They’ve been a huge part of the accelerated growth we’ve seen in the past decade.

Many shared this view, e.g., in 2008, strategic-management scholar Robert Grant writes:

Under Welch, GE went from strength to strength, achieving spectacular growth, profitability, and shareholder return. This performance can be attributed largely to the management initiatives inaugurated by Welch.

In 2005, a Manchester U. team led by Julie Froud reviewed the over fifty books and countless articles by management experts on GE in the Welch era. Work of Froud’s team debunked the mythology of credit given to the initiatives, finding a repeated pattern in that literature of blatantly confusing correlation with causation. Consistently––but incompetently––writers first cited GE’s inarguably impressive business results, then juxtaposed them with the initiatives––implying causality. For example, the team cites 2003 work by Paul Strebel of Swiss IMD Business School:

Strebel’s first shot announces GE’s undisputed achievement which is “two decades of high powered growth” … In the second shot, Strebel identifies key initiatives… as “trajectory drivers” that allowed the company to engineer upward shifts in “product/market innovation.”

However, the initiatives did not cause GE’s profitable growth of this era. If they had, we should find similar, dramatic growth across GE’s major business-sectors––since the initiatives were implemented throughout GE. Its product-business sector consisted of Power, Consumer, Medical Imaging, Aircraft Engines, Plastics, and Broadcasting. Its financial-business sector was GEC. As shown below, these two sectors in 1980-2000 grew at radically different rates. Product-businesses grew by +175%––merely in line with other US manufacturers––while GEC grew at the astounding rate of more than +7,000%.

GE Sales (Nominal $) by sector––1980-2000

|

Total-GE––Product-Bus’s + GEC |

GE Product-Businesses |

GEC (Financial Businesses) |

| 1980––$ Billions |

25.0 |

24.0 |

0.9 |

| 2000––$ Billions |

132.2 |

66.0 |

66.2 |

| Growth––$B (%) |

107.2 (530) |

42.0 (275) |

65.2 (7,108) |

Source (this and next three tables): GE Annual Reports, Froud et al, & author’s calculations

GE’s product-businesses also grew in this period, but only cyclically and dramatically slower than GEC. They grew at least 10% in only four of these twenty years, with average annual growth less than 6%. In contrast, GEC grew more than 10% every year but one (1994) with average annual growth over 26% and strong growth throughout (except 1994).

Average Annual Growth (%) by Sector––1981-2000

|

Total-GE: Product-Bus’s + GEC |

GE Product-Businesses |

GEC (Financial Businesses) |

| 1981-2000 |

8.9 |

5.7 |

26.7 |

| 1981-1990 |

9.3 |

6.7 |

36.6 |

| 1991-2000 |

8.6 |

4.7 |

16.7 |

| 1995-2000 |

13.7 |

8.6 |

22.3 |

GE Real Sales (2001 Prices, net of inflation) by sector––1980-2000

|

Total-GE: Product-Bus’s + GEC |

GE Product-Businesses |

GEC (Financial Businesses) |

| 1980––$ Billions |

57.4 |

54.4 |

3.0 |

| 2000––$ Billions |

141.5 |

72.5 |

69.0 |

| Growth $B (%) |

84.1 (246) |

18.1 (133) |

66.0 (2,280) |

| CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) |

4.6% |

1.4% |

16.9% |

| Real GEC-Growth as % of Real Total-GE Growth (66.0/84.1) |

78% |

Thus, most GE real-growth in this era traced to GEC. In contrast to GEC’s more-than-2,100% real-growth, the product-businesses’ 33% paled. Those businesses’ Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in real revenues was only 1.4%, while GEC’s was 16.9% and its $66 billion real-growth was 78% of total-GE’s $84 billion real-growth. Clearly, GE’s 1981-2000 by-sector results refute the standard, initiatives-focused GE narrative.

GE’s great, profitable growth during this period primarily reflected––not the Welch initiatives––but his real, hybrid strategy. To comprehend GE’s phenomenal rise, and eventual decline, today’s managers need to understand that hybrid strategy.

A Hybrid Product/Financial-Business––the Real Welch-Strategy

In 1987, GECC was renamed GE Capital Services––“Capital” to many and here simply termed GEC. By then it had evolved into a large, fast-growing multi-unit financial-business, with $3.9 billion revenues––about 10% of total GE. As Froud et al discuss, GEC had developed a wide range of financial services, including for example:

1967––the start of airline leasing with USAir; subsequently leading to working capital loans for distressed airlines [1980s] … By 2001…managed $18 billion in assets

1983––issues private-label credit card for Apple Computer; first time a card was issued for a specific manufacturer’s product

1980s––employers’ insurance, explicitly to help offset cyclicality in the industrial businesses

1980s––became a leader in development of the leveraged buyout (LBO)

1992––moved into mortgage insurance

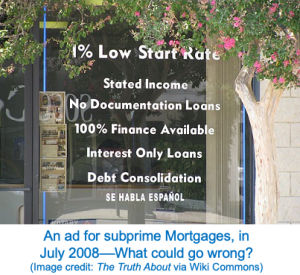

1980s-90s––one of largest auto finance companies…and [briefly] sub-prime lending in autos

Though quietly leading total-GE growth throughout the Welch era, GEC was not centrally featured in GE’s primary narrative, which focused mostly on total-GE and the Welch initiatives. Nonetheless, the world increasingly noticed that GE’s initially-small financial-business––not just total-GE––was growing explosively, requiring its own explanation.

world increasingly noticed that GE’s initially-small financial-business––not just total-GE––was growing explosively, requiring its own explanation.

Thus, to explain its spectacular growth, a secondary narrative emerged emphasizing GEC’s entrepreneurial, growth-obsessed perspective, derived from GE. There is some truth in this explanation––although GEC was a financial-business, it proactively applied GE’s depth of product-business experience and skill. By 1984, Thomas Lueck in the NY Times had noted that, “…Mr. Wright said that his executives are able to rely heavily on technical experts at General Electric to help them assess the risk of different businesses and product lines.” Later, in 1998, John Curran in Fortune primarily explainsGEC’s success in such terms of experience and skills:

The model is complex, but what makes is succeed is not: a cultlike obsession with growth, groundbreaking ways to control risk, and market intelligence the CIA would kill for… [GEC CEO Wendt] readily acknowledges the benefits Welch has brought to every corner of GE: a low-cost culture and the free flow of information among GE’s divisions, which gives Capital access to the best practices of some of the world’s best industrial businesses…

All five of Capital’s top people are longtime GE employees [including three] from GE’s industrial side… This unusual combination of deal-making skill and operations expertise is one of the keys to Capital’s success. Capital not only buys, sells, and lends to companies but also, unlike love ’em and leave ’em Wall Street, excels at running them. … Says Welch: “It is what differentiates [GEC] from a pure financial house.” [GEC’s] ability to actually manage a business often saves it from writing off a bad loan or swallowing a leasing loss.

Continuing, Curran focuses on GEC’s growth-obsession, especially via acquisitions:

The growth anxiety is pervasive… Says Wendt: “I tell people it’s their responsibility to be looking for the next opportunity…” Capital’s growth comes in many forms, but nothing equals the bottom-line boost of a big acquisition. Says [EVP] Michael Neal: “I spend probably half my time looking at deals, as do people like me, as do the business leaders.”Over the past three years Capital has spent $11.8 billion on dozens of acquisitions.

Moreover, we should not underestimate the skill that GE displayed in using acquisitions to build its huge, complex collection of financial businesses. Major misjudgments “would have undermined GE’s financial record,” Froud et al write, explaining that:

By way of contrast, Westinghouse, GE’s conglomerate rival, had its finance arm liquidated by the parent company after losing almost $1 billion in bad property loans in 1990.

Therefore, these entrepreneurial, growth focused product-business skills clearly gave GEC an advantage over competing financial companies, thus helping it succeed. However, its leaders, including Bossidy, Wright, Wendt, and Welch, had the insight to see that GEC could also enjoy two other, decisive advantages over financial-business competitors. These two advantages, much less emphasized in popular explanations of GEC’s success, were its lower cost-of-borrowing and its greater regulatory-freedom to pursue high returns.

Profitability of a financial-business is determined by its “net interest spread.” This spread is the difference is between the business’ cost-of-borrowing––or cost-of-funds––and the returns it earns by providing financial services––i.e., by lending or investing those funds. GEC’s and thus GE’s growth, until a few years after 2000, was enabled by the combination of its entrepreneurial, growth-focused skills and––most importantly––the two key advantages it enjoyed on both sides of this crucial net-interest-spread.

GEC’s cost-of-borrowing advantage––via sharing GE’s credit-rating

Of course, a business’ credit rating is fundamental to its cost-of-borrowing. During and largely since the Welch era, the norms of credit-rating held that a business belonging to a larger corporation would share the latter’s credit rating––so long as that smaller business’ revenues were less than half those of the larger corporation. Thus, GEC during the Welch era shared GE’s exceptionally high––triple-A or AAA––credit rating. It thus held a major cost-of-borrowing advantage over most other financial-business competitors.

GE’s own triple-A rating reflected the extraordinary financial strength and reliability of its huge, traditional product businesses. As Froud et al write in 2005:

GE Industrial may be a low growth business but it has high margins, is consistently profitable over the cycle… This solid industrial base is the basis for GE’s AAA credit rating, which allows [GEC] to borrow cheaply the large sums of money which it lends on to…customers.

In 2008, Geoff Colvin writes in Fortune that while GEC helps GE by financing customers:

In the other direction, GE helps GE Capital by furnishing the reliable earnings and tangible assets that enable the whole company to maintain that triple-A credit rating which is overwhelmingly important to GE’s success. Company managers call it “sacred” and the “gold standard.” Immelt says it’s “incredibly important.”

That rating lets GE Capital borrow funds in world markets at lower cost than any pure financial company. For example, Morgan Stanley’s cost of capital is about 10.6%. Citigroup is about 8.4%. Even Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has a capital cost of about 8%. But GE’s cost is only 7.3%, and in businesses where hundredths of a percentage point make a big difference, that’s an enormously valuable advantage. [emphasis added]

While GEC maintained it, the triple-A rating––and thus, generally, lower cost-of-borrowing––was a highly valuable advantage. It allowed GEC to grow rapidly by profitably delivering superior value propositions to customers, in the form of various financial services at competitively lower costs––interest and fees. It also provided low-cost funding to enable GEC’s aggressive, serial acquisition of new companies, thus further helping GEC rapidly expand. However, sustainability of this credit-rating relied on GEC not reaching 50% of total GE’s size. Yet, GEC would approach that limit by about 2000 if it continued its torrid growth. As The Economist writes in late 2002:

As GE Capital has grown (from under 30% of the conglomerate’s profits in 1991 to 40% in 2001), its prized triple-A credit rating has come under pressure… rating agencies say that they like the way GE manages its financial businesses. But they make it clear that GE can no longer allow GE Capital to grow faster than the overall company without sacrificing the triple-A badge. (Only nine firms still have that deep-blue-chip rating.) No matter how well run, financial firms are riskier than industrial ones, so the mix at GE must be kept right, say the agencies. As usual, the agencies seem to be behind the game: the credit markets already charge GE more than the average for a triple-A borrower.

The strength of this rating declined in the rest of that decade. By 2008, many investors doubted GE’s triple-A rating. As Colvin continues:

The credibility of bond ratings in general tumbled when it was revealed that securitized subprime mortgages had been rated double- or triple-A. GE’s rating clearly meant nothing to investors who bid credit default swaps on company bonds…. The message of the markets: The rating agencies can say what they like; we’ll decide for ourselves.

Finally, GE would lose its triple-A rating as the financial crisis unfolded, in 2009. Nonetheless, GEC’s credit-rating and thus borrowing-cost advantage had been a key factor in its success until 2008 and especially in the 1981-2000 Welch era.

GEC’s returns advantage––via sharing GE’s regulatory-classification

Though less-widely known than its cost-of-borrowing advantage, GEC also held a second major advantage––greater regulatory freedom to earn high returns on its services. In this era, businesses were classified––for purposes of financial regulation––as either financial or industrial (i.e., non-financial). Though clearly selling financial services, GEC––by virtue of being a part of GE––was allowed to share the corporation’s “industrial” regulatory-classification. Echoing the credit-rating rules, GEC could sustain this classification so long as its revenues stayed below 50% of total-GE’s.

With that classification, GEC was largely free from the financial regulations facing its competitors. As early as 1981, Leslie Wayne writes in the NY Times, GEC’s “…success has drawn the wrath of commercial bankers who compete against it but face Government regulations that [GEC] does not.” The bankers had a point, still valid twenty years later. Some of these costly and restrictive regulatory requirements––faced by GEC’s competitors but avoided by GEC––included: levels of financial reserves; ratios of assets-to-liabilities; and the Federal Reserve’s oversight and monitoring of asset quality-and-valuation. Moreover, GEC’s industrial-classification gave it more freedom to aggressively expand via acquisitions and divestitures, as Leila Davis and team at U Mass, in 2014, write:

Laxer regulation compared to [that for] traditional financial institutions has allowed GE to move into (and out of) a wider spectrum of financial services, with considerably less regulatory attention, than comparable financial institutions.

However, GEC’s regulatory freedom via its industrial-classification let it save costs but only by exposing the company to higher financial risks––against which the regulations had been intended to protect “financial” businesses. GEC’s industrial classification left it freer than competitors to earn high returns, unless and until related higher risks came home to roost––as they did in 2008. An example of saving costs but increasing risk was the restructuring of GE’s balance-sheet in this era, in favor of debt. As Froud et al explain:

Because GE does not have a retail banking operation it needs large amounts of debt finance to support its activities of consumer and commercial financing. Thus, the decision to grow [GEC] has resulted in a transformation in GE’s balance sheet. Most of the extra capital comes in the form of debt not equity: at the consolidated level, equity has fallen from around 45 per cent of long term capital employed in 1980 to around 12 per cent by the late 1990s… Almost all of the liabilities are associated with GECS. This restructuring…has been achieved throu gh very large issues of debt: for example, in 1992, Institutional Investor estimated that GE issued $5 to $7bn of commercial paper [a form of inexpensive short-term financing] every day…

gh very large issues of debt: for example, in 1992, Institutional Investor estimated that GE issued $5 to $7bn of commercial paper [a form of inexpensive short-term financing] every day…

This growth in debt would typically impose costs and constraints on a company classified as “financial” but GEC’s industrial classification let it avoid most of this burden, at least until the early 2000s. This higher debt, however, did increase the level of interest-rate and other risk faced by GEC. Yet, for over twenty years there was little challenge heard to this financial restructuring. After all, GE-and-GEC results were consistently outstanding in this era, and as Froud’s team write, analysts may not have fully understood the GEC numbers:

GE is generally followed by industrial analysts because it is classed as an industrial, not a financial firm… Arguably most industrial analysts will have limited ability to understand [GEC], whose financial products and markets are both bewilderingly various and often disconnected from those in the industrial businesses.

This silence, however, was finally broken by an investor outside the analyst community, in 2002 when, as Alex Berenson writes in NY Times:

William Gross, a widely respected bond fund [PIMCO] manager, sharply criticized General Electric yesterday, saying that G.E. is using acquisitions to drive its growth rate and is relying too much on short-term financing. “It grows earnings not so much by the brilliance of management or the diversity of their operations, as Welch and Immelt claim, but through the acquisition of companies––more than 100 companies in each of the last five years––using… GE stock or cheap…commercial paper” … Though the strategy appears promising in the short run, it increases the risks for G.E. investors in the long run, he said. If interest rates rise or G.E. loses access to the commercial paper market, the company could wind up paying much more in interest, sharply cutting its profits.

Gross suggests in Money CNN that GE ignored financial regulatory-requirements:

“Normally companies that borrow in the [commercial paper] market are required to have bank lines at least equal to their commercial paper, but GE Capital has been allowed to accumulate $50 billion of unbacked [commercial paper] …” Gross said.

Of course, GEC could legally disregard this financial regulatory-requirement, thanks to its industrial classification––it was regulated as an industrial, not a financial business. Froud et al add that, “Overall Gross stated that he was concerned that GE, which should be understood as a finance company, was exposed to risks that were poorly disclosed.” Markets briefly reacted to this criticism, but GE weathered the storm easily enough.

As of 2000, the hybrid strategy had successfully produced the company’s legendary, profitable growth. However, two key aspects of GE’s situation had also changed for the worse. During the Welch era GE had significantly reduced its emphasis on product innovation. At the same time, the twenty-year lifetime of growth produced by the hybrid strategy was coming to its inevitable end. Storm clouds would soon enough hover over GE.

Deemphasis on product-innovation during the Welch era

Under Welch and the hybrid strategy, GE missed a huge opportunity to fully extend its great tradition of product-innovation into some of the most important and––for GE, intuitively obvious––electrical markets. These included computers, software, semiconductors, and others––dismissed by Welch and team as bad businesses for GE, in contrast to the “more promising” financial businesses that “seemed an easy way to make money.” Yet, those neglected electrical businesses, despite the need to “invest heavily in R&D, build factories, and bend metal day after day,” evolved into today’s world-dominating digital technologies, where GE might have later become a leader, not spectator.

GE did not wholly abandon product-innovation during the Welch era, as the company continued making significant incremental innovations in its core industrial businesses of power, aviation, and medical imaging. Nonetheless, complementing GE’s failure to create new businesses in the emerging digital-technology markets, the company seemed to deemphasize product innovation generally––apparently carried away by the giddy excitement of rapidly accelerating financial services. Some observers have agreed; for example, Rachel Silverman in the WSJ writes in 2002:

In recent decades, much of GE’s growth has been driven by units such as its NBC-TV network and GE Capital, its financial-services arm; the multi-industrial titan had shifted focus toward short-term technology research…Some GE scientists had been focusing on shorter-term, customer-based projects, such as developing a washing machine that spins more water out of clothes. That irked some of the center’s science and engineering Ph.D.’s, who thought they were spending too much time fixing turbines or tweaking dishwashers. Some felt frustrated by the lack of time to pursue broader, less immediate kinds of scientific research…”Science was a dirty word for a while,” says Anil Duggal, a project leader…

Steve Lohr writes in 2010 in the NY Times:

Mr. Immelt candidly admits that G.E. was seduced by GE Capital’s financial promise––the lure of rapid-fire money-making unencumbered by the long-range planning, costs and headaches that go into producing heavy-duty material goods. Other industrial corporations were enthralled with finance, of course, but none as much as G.E., which became the nation’s largest nonbank financial company.

James Surowiecki writes in The New Yorker in 2015:

In the course of Welch’s tenure, G.E.’s in-house R. & D. spending fell as a percentage of sales by nearly half. Vijay Govindarajan, a management professor at Dartmouth…told me that “financial engineering became the big thing, and industrial engineering became secondary.” This was symptomatic of what was happening across corporate America: as Mark Muro, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, put it to me, “The distended shape of G. E. really reflected twenty-five years of financialization and a corporate model that hobbled companies’ ability to make investments in capital equipment and R. & D.”

Later still, USC’s Gerard Tellis in Morning Consult in 2019 argues in retrospect that “GE rose by exploiting radical innovations,” adding that:

The real difference between GE on the one hand and Apple and Amazon on the other is not industry but radical innovation.GE focused on incremental innovations in its current portfolio of technologies. Apple and Amazon embraced radical innovations, each of which opened new markets or transformed current ones. [Managers should:] Focus on the future rather than the past; target transparent innovation-driven growth rather than manipulate cash; and strive for radical innovations rather than staying immersed in incremental innovations.

So, GE’s product-innovation capabilities decayed somewhat under Welch. Still. the hybrid strategy was undeniably effective, so we can speculate about whether GE might have found a better way to use it. Perhaps GE could have still leveraged the product-businesses’ strengths to grow GEC, but not deemphasize those businesses’ delivery of superior-value via customer focused, science based, synergistic product-innovation.

Yet, a revised hybrid-strategy would have likely still struggled. It would have presented the same financial risks that GE badly underestimated. Its focus on financial services––so different from the product-businesses––would have still created strategic incoherence for GE. Probably most crucial, such a revised strategy would have required a robust, renewed embrace of the above fundamental product-innovation principles that GE had developed and applied in its first century––so different from the GE that evolved under Welch.

This decay in product-innovation capabilities did not prevent the company from achieving its stellar financial results through 2000. However, GE could find itself in a dead-end should the hybrid strategy falter after 2000––which soon enough it did.

Dead-end finale for GE’s unsustainable triumph––2001-2009

In 2000, at the peak of the Welch-led triumph, GE’s rapid, profitable growth seemed likely to continue indefinitely. However, perpetual-motion machines never work, and GEC was no exception. In the first decade of the new millennium, the ingenious hybrid strategy began leading GE––inevitably––into a dead end.

Almost immediately after Welch retired, Immelt and GE felt pressure, as market confidence was shaken by a series of events––the burst of the dot-com bubble, the Enron collapse, various other accounting scandals, and not least the 9/11 attack. The company’s stock price fell and by 2002 its market-value was only 43% of its 2000 peak. GE soon regained its footing and began growing again after 2003, recovering to about 65% of that 2001 market-value peak by 2006. However, the company had lost the magic of the hybrid strategy and failed to adjust.

In the two decades of the Welch era, this strategy had quietly turbo-charged the growth of GEC––which in turn drove total-GE’s spectacular, widely-celebrated profitable growth. To perform this remarkable trick, the hybrid strategy had enabled two crucial advantages for GEC––a lower cost-of-borrowing (via sharing GE’s triple-A credit rating) and more freedom-to-earn-high returns (via sharing GE’s regulatory classification). However, these key advantages depended on keeping GEC’s revenues below 50% of total-GE, a limit nearly reached––49%––by 2000. GE leadership understood that they now had two options––cut GEC’s growth or dramatically accelerate the product-businesses.

Since GEC had long been the goose that laid golden eggs, GE was naturally loath to throttle it back. Thus, accelerating the product-businesses was preferable. Indeed, during GE’s first century––preceding Welch––the company had repeatedly expanded and created major new product-businesses. It had done so largely by delivering superior value to customers, led by science-based, synergistic product-innovation. However, GE under Welch had lost much of that product-innovation habit in its product-businesses. These were now managed, instead, for earnings, mostly via slow growth and relentless cost-savings––what Jack called “productivity.” To suddenly generate major new growth of the product-businesses––enough to make up for GEC’s previous, exceptionally-high growth––might have been possible, but a tall order. Moreover, to do so via organic growth––rather than by acquisition––would have been even more challenging.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Welch and successor Jeff Immelt–– to keep the hybrid-strategy growth-engine running––turned to giant industrial acquisitions. Indeed, Welch had hoped to cap his career in 2000 with an enormous $45 billion acquisition of Honeywell. That would have added $25 billion in revenues to GE’s product-businesses, reducing the financial-businesses’ 49% share of GE––down to 41%. That would have bought three-to-four more years during which GEC could have continued growing at its late 1990s rate before again reaching the 50%-of-total-GE limit.

If this tactic had worked, Welch and Immelt likely imagined that GE could repeat it every few years with another block-buster acquisition. GE’s efforts to grow might have thus evolved into no-more than a serial reliance on acquisition––like many essentially-failed, imagination-challenged conglomerates since the 1960s. However, before even that dubious plan could be realized, the European regulators blocked the Honeywell deal, based on anticompetitive concerns, which some––e.g., NY Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin––suggested had been clear from the outset, but ignored by Welch. Undismayed, as Drake Bennett in Bloomberg wrote in 2018, Immelt after 2000 pursued other large, industrial prey:

He made a series of acquisitions [e.g., 2003––$5.5 billion Vivendi-Universal, $9.5 billion Amersham]. These proved more expensive and less synergistic than promised. Scott Davis, a longtime GE analyst…calculated that GE’s total return on Immelt’s acquisitions has been half what the company would have earned by simply investing in stock index mutual funds.

Shown below are GE revenue-results in real-dollars by major segment, from 2000 until just before the impact of the 2008-09 financial crisis. In this period, Immelt and team had to constrain GEC’s growth to stay within the mandatory 50%-of-total-GE limit. Indeed, in real-dollars GEC declined, with a -1.9% CAGR. Aside from acquisitions, GE still needed growth, no longer just earnings, from the product-businesses. Immelt thus increased R&D spending and likely squeezed those businesses less for cost savings. Their growth responded, increasing from 1.4% CAGR in the 1981-2000 period to 2.3% in the 2000-2008 period. However, this increase could not replace GEC. In contrast to total-GE’s 1980-2000 real-sales CAGR of 4.6%, the 8 years 2000-08 real-sales CAGR was only 0.36%.

GE Real Sales (2012 Prices) by sector––2000-2008

|

Total-GE: Product-Bus’s + GEC |

GE Product-Businesses |

GEC (Financial Businesses) |

| 2000––$ Billions |

167.9 |

83.8 |

84.1 |

| 2008––$ Billions |

172.9 |

100.8 |

72.1 |

| Growth $B (%) |

5.0 (103) |

17.0 (120) |

-12.0 (86) |

| CAGR |

0.36% |

2.3% |

-1.9% |

After about four years of feeling pressure, lacking a reliable basis for growth, Immelt and team unsurprisingly began to take additional risks. In 2014, The Economist commented that, “in his early years as boss, Mr. Immelt let the financial side continue to swell.” GE had benefited earlier from a bubble in gas-turbine demand, and now:

After about four years of feeling pressure, lacking a reliable basis for growth, Immelt and team unsurprisingly began to take additional risks. In 2014, The Economist commented that, “in his early years as boss, Mr. Immelt let the financial side continue to swell.” GE had benefited earlier from a bubble in gas-turbine demand, and now:

As another bubble inflated, in housing, GE Capital expanded its mortgage lending, bought up corporate debt and muscled into commercial property, all of which left it horribly exposed when Lehman Brothers’ collapse in September 2008 led to a markets meltdown.

Continuing in 2014, Davis et al at U Mass write:

In 2004, GE moved into the subprime mortgage industry with the acquisition of Western Mortgage Company (WMC). When GE divested [WMC] in 2007 after the subprime bubble burst ([GE] losses estimated at more than one billion dollars), [GEC] was the tenth-largest subprime mortgage lender in the U.S.—ranking above well-known examples of financial companies including Lehman Brothers, Citigroup, and Wachovia…

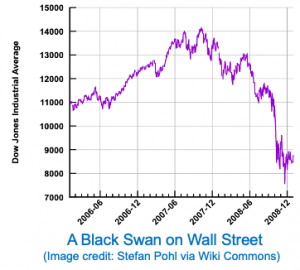

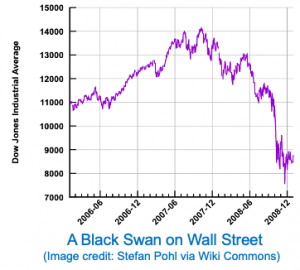

In 2008, the commercial-paper market froze––confirming Gross’ concerns and creating a temporary crisis for GE which suddenly could not roll over its short term debt. GE and the world was seeing the appearance of a Black Swan––the term Nassim Taleb coined for highly unpredictable events of massive impact. In this case, the black swan was the global financial crisis. In March 2009, as Gryta and Mann write later in the Wall Street Journal:

In 2008, the commercial-paper market froze––confirming Gross’ concerns and creating a temporary crisis for GE which suddenly could not roll over its short term debt. GE and the world was seeing the appearance of a Black Swan––the term Nassim Taleb coined for highly unpredictable events of massive impact. In this case, the black swan was the global financial crisis. In March 2009, as Gryta and Mann write later in the Wall Street Journal:

General Electric was on the brink of collapse. The market for short-term loans, the lifeblood of GE Capital, had frozen, and there was little in the way of deposits to fall back on. The Federal Reserve stepped in to save it after an emergency plea from Immelt.

* * *

The Welch hybrid-strategy had taken GE to the apex of its triumph in 2000. Continued by Immelt, this strategy had then taken GE to a dead-end. It could no longer drive growth by priming GEC; at the same time, after letting GE’s product-innovation capabilities atrophy for over two decades, the product-businesses could not pick up the slack. GE would partially recover in the next few years, only to stumble again after 2015. The great company was not dead but had lost its way.

In the next part of this blog, Part Three, we explore GE’s Digital Delusions. This would be Immelt’s attempt to replace the financially-driven Welch strategy with a new grand but unrealistic vision of GE as a tech giant for the industrial world. That Part Three post will be followed by Energy Misfire––Part Four. Not yet published, that final post in this GE Series will focus on GE’s failure after 2001 to create a new, viable global strategy for energy, missing its greatest opportunity of the past fifty years in the process.