Big Data Can Help Execute

But Not Discover New Growth Strategies

By Michael J. Lanning––Copyright © 2017-18 All Rights Reserved

Business investment in “big data analytics” (or “big data”) continues growing. Some of this growth is a bet that big data will not only improve operations, but reveal hidden paths to new breakthrough growth strategies. This bet rests partly on the tech giants’ famous use of big data. We have recently seen the emergence, in part also using big data, of major new consumer businesses, e.g., Uber and Airbnb––discussed in this second post of our data-and-growth-strategy series. Again using big data, some promising growth-strategies have also emerged recently in old industrials, including GE and Caterpillar (discussed in our next post). Many thus see big data as a road map to major new growth.

Typical of comments on the new consumer businesses, Maxwell Wessell’s HBR article, How Big Data is Changing Disruptive Innovation, called Uber and others “data-enabled disruptions.” Indefatigable big-data-fan Bernard Marr wrote that Uber and Airbnb were only possible with “big data and algorithms that drive their individual platforms… [or else] Uber wouldn’t be competitive with taxi drivers.” McKinsey, late 2016, wrote, “Data and analytics are changing the basis of competition. [Leaders] launch entirely new business models…[and] the next wave of disruptors [e.g. Uber, Airbnb are] … predicated on data and analytics.” MIT’s SMR Spring 2017 report, Analytics as Source of Business Innovation, cited Uber and Airbnb as “poster children for data-driven innovation.”

Like a compass, big data only helps once you have a map––a growth-strategy. To discover one, first “become the customer”: explore and analyze their experiences; then creatively imagine a superior scenario of experiences, with positives (benefits), costs, and any tradeoffs, that in total can generate major growth. Thus, formulate a “breakthrough value proposition.” Finally, design how to profitably deliver (provide and communicate) it. Data helps execute, not discover, new growth strategies. Did Uber and Airbnb use data to discover, not just execute, their strategies? Let’s see how these discoveries were made.

Uber

Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick co-founded Uber. Its website claims that, in Paris in late 2008, the two “…had trouble hailing a cab. So, they came up with a simple idea—tap a button, get a ride.” Kalanick later made real contributions to Uber, but the original idea was Garrett Camp’s, as confirmed by Travis’ 2010 blog, and his statement at an early event (quoted by Business Insider) that “Garrett is the guy who invented” the app.

However, the concept did not just pop into Camp’s mind one evening. As described below, the idea’s genesis was in his and friends’ frustrating experiences using taxis. He thought deeply about these, experimented with alternatives, and imagined ideal scenarios––essentially the strategy-discovery methodology mentioned above, and that which we call, “become the customer.” He then recognized, from his own tech background, the seeds of a brilliant solution.

Camp was technically accomplished. He had researched collaborative systems, evolutionary algorithms and information retrieval while earning a Master’s in Software Engineering. By 2008 he was a successful, wealthy entrepreneur, having sold his business, StumbleUpon, for $75M. This “discovery engine” finds and recommends relevant web content for users, using sophisticated algorithms and big data technologies.

As Brad Stone’s piece on Uber in The Guardian recounted earlier this year, the naturally curious Camp, then living in San Francisco, had time to explore and play with new possibilities. He and friends would often go out for dinner and bar hopping, and frequently be frustrated by the long waits for taxis, not to mention the condition of the cars and some drivers’ behavior. Megan McArdle’s 2012 Atlantic piece, Why You Can’t Get a Taxi, captured some of these complaints typical of most large cities:

Why are taxis dirty and uncomfortable and never there when you need them? Why is it that half the time, they don’t show up for those 6 a.m. airport runs? How come they all seem to disappear when you most need them—on New Year’s Eve, or during a rainy rush hour? Women complain about scary drivers. Black men complain about drivers who won’t stop to pick them up.

The maddening experience of not enough taxis at peak times reflected the industry’s strong protection. For decades, regulation limited taxi licenses (“medallions”), constraining competition, and protecting revenue and medallion value. The public complained, but cities’ attempts to increase medallions always met militant resistance; drivers would typically protest at city hall. And if you didn’t like your driver or car, you could leave no tip or complain, but not with any real impact.

Irritated, Camp restlessly searched for ways around these limits. As hailing cabs on the street was unreliable, he tried calling, but that was also problematic. Dispatchers would promise a taxi “In 10 minutes” but it often wouldn’t show; he’d call again but they might lie or not remember him. Next, he started calling and reserving them all, taking the first to arrive, but this stopped working once they blacklisted Camp’s mobile phone.

He then experimented with town-cars (or “black cars”). These were reliable, clean and comfortable, with somewhat more civil drivers, though more expensive. However, as he told Stone, their biggest problem exacerbating their cost was filling dead-time between rides, which to a lesser degree also affected regular taxis. As McArdle wrote, “Drivers turn down [some long-distant fares since] they probably won’t get a return fare, and must instead burn time and gas while the meter’s off” which can wipe out the day’s profit.

Camp could now imagine much better ride-hailing experiences, but how to implement this vision? Could technology somehow balance supply and demand, and improve the whole experience for riders  and drivers? At that moment (as he later told Stone) Camp recalled a futuristic James Bond scene he loved and often re-watched, from the 2006 Casino Royale. While driving, Agent 007’s phone shows an icon of his car, on a map, approaching The Ocean Club, his destination. Camp immediately recognized that such a capability could bring his ride-hailing vision to life.

and drivers? At that moment (as he later told Stone) Camp recalled a futuristic James Bond scene he loved and often re-watched, from the 2006 Casino Royale. While driving, Agent 007’s phone shows an icon of his car, on a map, approaching The Ocean Club, his destination. Camp immediately recognized that such a capability could bring his ride-hailing vision to life.

When iPhone was launched in 2007 it not only included Google Maps, but Camp knew it also had an “accelerometer” which let users know if their car was moving. Thus, the phone could function like a taxi meter, charging for time and distance. And in Summer of 2008, Apple had also just introduced the app store.

Camp knew this meant he could invent a “ride-hailing app” that would deliver benefits––positive experiences. With it, riders and drivers would digitally book a ride, track and see estimated arrival, optimize routes, make payments, and even rate each other. The app would also use driver and rider data to match supply and demand. This match would be refined by dynamic (“surge”) pricing, adjusting in real time as demand fluctuates. Peak demand would be a “tradeoff”: higher price but, finally, reliable supply of rides.

At this point, Camp grew more excited, sensing how big the concept might be, and pressed his friend Travis Kalanick to become CEO (Camp would refocus on StumbleUpon). Despite Kalanick’s famous controversies (ultimately leading to his stepping down as CEO) many of his decisions steered Uber well. Camp’s vision still included fleets of town-cars, which Kalanick saw as unnecessary cost and complexity. Drivers should use their own cars, while Uber would manage the driver-rider interface, not own assets. Analyzing the data, Kalanick also discovered the power of lower pricing: “If Uber is lower-priced, then more people will want it…and can afford it [so] you have more cars on the road… your pickup times are lower, your reliability is better. The lower-cost product ends up being more luxurious than the high-end one.”

With these adjustments, Uber’s strategy was fully developed. Camp and later Kalanick had “become the customer,” exploring and reinventing Uber’s “value propositions” ––the ride-hailing experiences, including benefits, costs and tradeoffs, that Uber would deliver to riders and drivers. These value propositions were emerging as radically different from and clearly superior to the status quo. It was time to execute, which required big data, first to enable the app’s functionalities. Kalanick also saw that Uber must expand rapidly, to beat imitators into new markets; analytics helped identify the characteristics of likely drivers and riders, and cities where Uber success was likely. Uber became a “big data company,” with analytics central to its operations. It is still not profitable today, and faces regulatory threats; so, its future success may increasingly depend on innovations enabled by data. Nonetheless, for today at least, Uber is valued at $69B.

Yet, to emulate Uber’s success, remember that its winning strategy was discovered not by big data, but by becoming its users. Uber studied and creatively reinvented key experiences––thus, a radically new value proposition––and designed an optimal way to deliver them. Now let’s turn to our second, major new consumer business, frequently attributed to big data.

Airbnb’s launch was relatively whimsical and sudden. It was not the result of frustration with an existing industry, as with ride-hailing. Rather, the founders stumbled onto a new concept that was interesting, and appealing to them, but not yet ready to fly. Their limited early success may have helped them stay open to evolving their strategy.

Airbnb’s launch was relatively whimsical and sudden. It was not the result of frustration with an existing industry, as with ride-hailing. Rather, the founders stumbled onto a new concept that was interesting, and appealing to them, but not yet ready to fly. Their limited early success may have helped them stay open to evolving their strategy.

They embarked on an extended journey to “become” their users, both hosts and guests; they would explore, deeply rethink, and reinvent Airbnb’s key customer-experiences and its value proposition. Big data would become important to Airbnb’s execution, but the evolutionary discovery of its strategy was driven by capturing deep insight into customer experiences. Providing and communicating its value proposition, Airbnb outpaced imitators and other competitors, and is valued today at over $30B. Like Uber, Airbnb is a great example of the approach and concepts we call “value delivery,” as discussed and defined in our overview, Developing Long-Term Growth Strategy.

In 2007, Joe Gebbia and Brian Cheskey, both twenty-seven and friends from Design school, shared a San Francisco apartment. They hoped for entrepreneurial opportunities, but needed cash when their rent suddenly increased. A four-day design conference was coming to town, and most hotels were booked. Gebbia suggested “turning our place into ‘designers bed and breakfast’–offering…place to crash…wireless internet…sleeping mat, and breakfast. Ha!” Next day, they threw together a web site, airbedandbreakfast.com. Surprisingly, they got three takers; all left happy, paying $80 per night (covering the rent). They all also felt rewarded by getting to hear each other’s stories; the guests even offered advice on the new business. Cheskey and Gebbia gave each other a look of, “Hmmm…” and a new business had been born.

The concept seemed compatible with the founders’ values; as The Telegraph later wrote, “Both wanted to be entrepreneurs, but [not] ‘create more stuff that ends up in landfill.’ …a website based on renting something that was already in existence was perfect…”

However, they first underestimated and may have misunderstood their concept. An early headline on the site read, “Finally, an alternative to expensive hotels.” Brian Chesky says:

We thought, surely you would never stay in a home because you wanted to…only because it was cheaper. But that was such a wrong assumption. People love homes. That’s why they live in them. If we wanted to live in hotels, more homes would be designed like hotels.

They were soon joined by a third friend, engineer Nathan Blecharczyk, who says that this mix of design and engineering perspectives [view 01:19-01:40 in interview]:

…was pretty unusual and I actually attribute a lot of our success to that combination. We see things differently. Sometimes it takes a while to reconcile those different perspectives but we find when we take the time to do that we can come up with a superior solution, one that takes into account both points of view.

Soon after the initial launch, they used the site frequently, staying with hosts, and gathering insights into experiences. Two key early discoveries were: 1) Payments, then settled in cash from guest to host, created awkward “So, where’s my money?” moments, and should be handled instead with credit card, through the Airbnb site; and 2) while they originally assumed a focus on events, when hotels are over-booked and expensive, users surprised them by asking about other travel, so they realized that they had landed in the global travel business. A 2008 headline read, “Stay with a local when traveling.”

In August of 2008, the team thought they had made a breakthrough. Obama would accept the Democratic nomination before 100,000 people in Denver, which only had 30,000 hotel rooms. So, Airbnb timed its second launch for the convention. Sure enough, they saw a huge booking spike…but it promptly dropped back to near-zero, days later.

Searching for a promotional gift for hosts, they pulled off a scrappy, startup stunt. They designed and hand-assembled 500 boxes of cereal, with covers they convinced a printer to supply for a share of sales: Obama Os (“Hope in every bowl”) and Cap’n McCain’s (“Maverick in each bite”). CNN ran a story on it, helping sell some at $40 per box, for over $30K total––enough to survive a few more months.

But mid-2009, they were still stalled, and about to give up. About fifteen investors all ignored Airbnb, or saw nothing in it. Then Paul Graham, a founder of “Y Combinator” (YC, a highly-regarded, exclusive start-up-accelerator), granted Airbnb his standard five-minute interview, which he spent telling them to find a better idea (“Does anyone actually stay in one of these? …What’s wrong with them?”) But on the way out the door, thinking all was lost anyway, Chesky handed a box of Obama Os to Graham, who asked, “What’s this?” When told, Graham loved this story of scrappy, resourceful unwillingness to die. If they could sell this cereal, maybe they can get people to rent their homes to strangers, too.

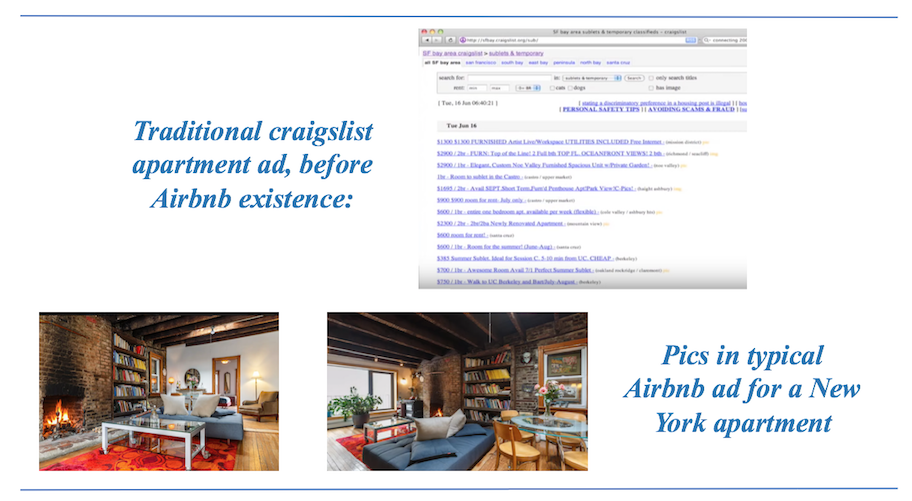

Joining YC led to some modest investments, keeping Airbnb alive. Still, weekly revenues were stuck at $200. Paul pushed them to analyze all their then-forty listings in their then-best market, New York. Poring over them, Gebbia says, they made a key discovery:

We noticed a pattern…similarity between all these 40 listings…the photos sucked…People were using their camera phones [of poor quality in 2009] or…their images from classified sites. It actually wasn’t a surprise that people weren’t booking rooms because you couldn’t even really see what it is that you were paying for.

Paul urged them to go to New York immediately, spend lots of time with the hosts, and upgrade all the amateur photography. They hesitated, fearing pro photography was too costly to “scale” (i.e., to use large-scale). Paul told them to ignore that (“do things that don’t scale”). They took that as license to simply discover what a great experience would be for hosts, and only worry later about scale economics. A week later, results of the test came in, showing far better response, doubling total weekly revenue to $400. They got it.

The team reached all 40 New York hosts, selling them on the (free) photos, but also building relationships. As Nathan Blecharczyk explains [view 18:50-21:27 in his talk], they could follow up with suggestions that they could not have made before, e.g., enhancements to wording in listings or, with overpriced listings, “start lower, then increase if you get overbooked.”

Of course, hi-res photography is common on websites today, even craigslist, and seems obvious now, as perhaps it is to think carefully about wording and pricing in listings. However, these changes made a crucial difference in delivering Airbnb’s value proposition, especially in helping hosts romance and successfully rent their home. This time-consuming effort greatly increased success for these hosts. After that, “people all over the world started booking these places in NY.” The word spread; they had set a high standard, and many other hosts successfully emulated this model.

To even more deeply understand user experiences, the team used “becoming the customer,” or what Gebbia calls, “being the patient,” shaped by his design-thinking background.

[As students, when] working on a medical device we would go out [and] talk with…users of that product, doctors, nurses, patients and then we would have that epiphany moment where we would lay down in the bed in the hospital. We’d have the device applied to us…[we’d] sit there and feel exactly what it felt like to be the patient…that moment where you start to go aha, that’s really uncomfortable. There’s probably a better way to do this.

As Gebbia explained, “being the patient” is still an integral piece of Airbnb’s culture:

Everybody takes a trip in their first or second week [to visit customers, document and] share back to the entire company. It’s incredibly important that everyone in the company knows that we believe in this so much…

They gradually discovered that hosts were willing to rent larger spaces, from air beds, to rooms, entire apartments, and houses. They also further expanded Airbnb’s role, such as hosting reviews and providing a platform for host/guest communications. “Becoming the customer,” they discovered a “personal” dimension of the experience; in 2011, Gebbia recounted [view 19:41-20:36] being a guest in “an awesome West Village apartment,” owned by a woman named Katherine (away then), and he was greeted with:

“Becoming the customer,” they discovered a “personal” dimension of the experience; in 2011, Gebbia recounted [view 19:41-20:36] being a guest in “an awesome West Village apartment,” owned by a woman named Katherine (away then), and he was greeted with:

…a very personalized welcome letter…a Metro Card for me, and [menus from] Katherine’s favorite take-out places…I just felt instantly like, ‘I live here!’ [And on the street] felt like I have an apartment here, I’m like a New Yorker! So, it’s this social connection…to the person and their spaces; it’s about real places and real people in Airbnb. This is what we never anticipated but this has been the special sauce behind Airbnb.

This idea of personal connection may have helped address Airbnb’s crucial problem of trust (“who is this host, or guest?”). Again, they thought deeply about the problem, both redesigning experiences and applying digital solutions. One was “Airbnb Social Connections,” launched in 2011. As TechCrunch wrote, a prospective guest can:

…hook up the service to your social graph via Facebook Connect. Click one button, opt-in, and [in] listings for cities around the world you’ll now see an avatar if a Facebook friend of yours is friends with the host or has reviewed the host. It’s absolutely brilliant.” [Cheskey said it also helps guests and hosts] “have something in common…and helps you find places to stay with mutual friends, people from your school or university…

To further build trust, users were required to “verify, meaning share their email…online and offline identify.” Hosts were asked “to include large photos of themselves on their profiles.” Hosts and guests were urged to communicate before each stay.

Next, the team searched for yet more dimensions of users’ positive experiences. As Leigh Gallagher wrote in Fortune, the team (in 2012) pondered, “Why does Airbnb exist? What’s it purpose?” The global head of community interviewed 480 employees, guests, and hosts, and they found that guests don’t want to be “tourists” but to engage with people and culture, to be “insiders.” The idea of “belonging” emerged, and a new Airbnb mission: “to make people around the world feel like they could ‘belong anywhere.’” Cheskey explains, “cities used to be villages. But…that personal feeling was replaced by ‘mass-produced and impersonal travel experiences,’ and along the way, ‘people stopped trusting each other.’”

They adopted the “Bélo” (as at right in the expanded icon)

to echo this idea.  Some mocked all this. TechCrunch

Some mocked all this. TechCrunch

declared it a “hippy-dippy concept”; others suggested that users just wanted a “cheap and cool place to stay,” not “warm and fuzzy” feelings. But Gallagher argues that “belonging” can be more substantive than, “having tea and cookies with [your host]”:

It was much broader: It meant venturing into neighborhoods that you might not otherwise be able to see, staying in places you wouldn’t normally be able to, bunking in someone else’s space, [experience] “hosted” for you, regardless of whether you ever laid eyes on him or her.

“Belonging” may have been a little warm and fuzzy, or even hokey, but Gallagher cites evidence that the idea seemed to resonate with many users. In late 2012, wanting to build further on this notion and having read an article in Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, Cheskey began thinking that Airbnb should focus more on “hospitality.” He read a book by Chip Conley, founder of a successful boutique-hotel chain. Conley wanted guests to check out, after three days, as a “better version of themselves”; he talked of democratizing hospitality, which had become “corporatized.” Airbnb hired him.

Conley gave talks to Airbnb hosts and employees worldwide, and established a “centralized hospitality-education effort, created a set of standards, and started a blog, a newsletter, and an online community center where hosts could learn and share best practices.” He also started a mentoring program in which experienced hosts could teach new ones about good hospitality. Examples of the new standards included:

- Before accepting guests, try to make sure their idea for their trip matches your “hosting style”; [e.g., if they want] a hands-on host and you’re private, it may not be the best match.

- Communicate often; provide detailed directions. Establish any “house rules” clearly.

- …beyond basics? [placing] fresh flowers or providing a treat upon check-in, like a glass of wine or a welcome basket. Do these things…even if you’re not present during the stay.

Airbnb took longer than Uber to discover their strategy, but they got there, again by climbing into the skin of users, “becoming the customer” (or “being” the patient”), living their users’ experiences. Like Uber, they then used big data extensively, to help execute. For example, building on the early New York experiments to help hosts set optimal prices, Airbnb used big data to create, as Forbes wrote, “Pricing Tips.” This “constantly updating guide tells hosts, for each day of the year, how likely it is for them to get a booking at the price they’ve currently chosen.” Airbnb’s machine-learning package further helps hosts quantitatively understand factors affecting pricing in their market.

In combination with the above initiatives to strengthen trust, personal connection, and even that sense of “belonging anywhere,” big data helped Airbnb continue to improve the value proposition it delivered. Its great strategic insights into user experiences, and its superb execution, allowed Airbnb to outdistance its imitative competitors.

So, both Uber and Airbnb made great use of big data. Yet, for both these game-changing businesses, to “become the customer” (or “being the patient”) was key to discovering the insights underlying their brilliant, breakthrough-growth strategies.

* * *

This post follows our first, Who Needs Value Propositions, in this data/strategy series. Our next post (#3–– Big Data as a Compass––Industrial/B2B Businesses) looks at the industrial examples mentioned earlier (GE and Caterpillar), to compare their lessons with those in the above consumer cases. We then plan three more posts in this series:

- #4: Dearth of Growth––Why Most Businesses Must Get Better at Discovering & Developing New Growth Strategies

- #5: No Need to Know Why? Historical Claims (“Correlation is all we need, Causality is obsolete”) Propagated Misplaced Faith in Big Data as fount of new growth strategies

- #6: Powerful for execution, big data is also prone to chronic, dangerous errors