4 Ways to Improve Delivering Profitable Value

Posted 4/13/15

Make Value Propositions the Customer-Focused Linchpin to Business Strategy

We suggest that Businesses should be understood and managed as integrated systems, focused single-mindedly on one thing – profitably delivering superior Value Propositions, what we call delivering profitable value (DPV). But most are not. Some readers may assume this discussion can only be a rehash of the obvious – surely everyone ‘knows’ what Value Propositions (VPs) are, and why they matter. But we suggest that most applications of the VP concept actually reflect fundamentally poor understanding of it, and fail to get the most out of it for developing winning strategies. In this post I’ll summarize 4 ways to improve on delivering profitable value, using the VP concept far more effectively – as the customer-focused linchpin to your strategy.

Delivering Profitable Value – Let’s first recap the key components of this approach:

Real & Complete Value Proposition – A key element of strategy; internal doc (not given to customers); as quantified as possible; makes 5 choices (discussed in depth here):

- Target customers (or other entities) for this VP?

- Relevant timeframe in which we will deliver this VP?

- What we want customers to do (e.g. buy/use and/or other behaviors/changes?)

- Their competing alternatives (competitors, status quo, new technologies, etc.)?

- Resulting experiences they will get & we deliver? Not a list of products & performance attributes, but the core of a VP; discussed here and further here, they are:

- Specific, measurable events/processes – outcomes – in customer’s life/business, that result from doing as we propose (e.g., buy/use products/services, etc.)

- Includes price and tradeoffs (inferior or equal experiences)

- All as compared to competing alternatives

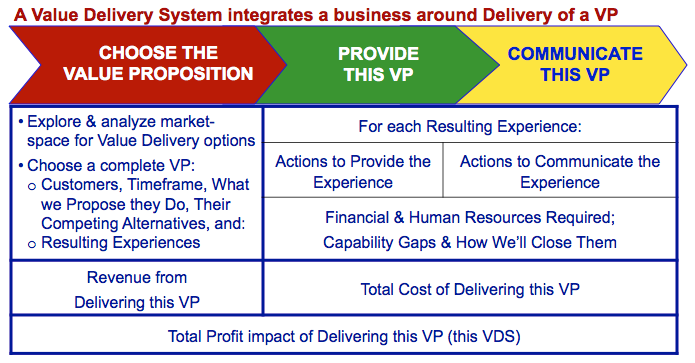

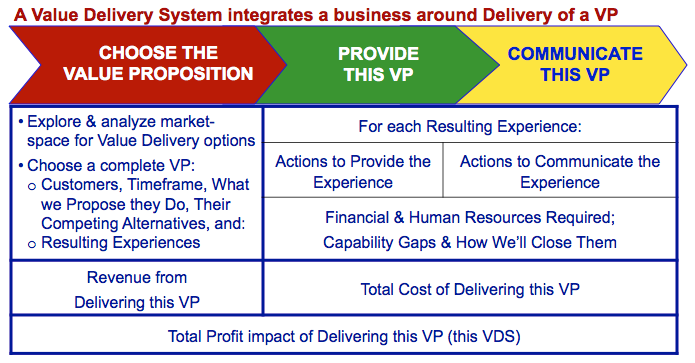

Deliver the chosen VP – A real VP identifies what experiences to deliver, not how; so manage each business as a Value Delivery System with 3 integrated high-level functions:

- Choose the VP (discover/articulate a superior VP focused on resulting experiences)

- Provide it (enable the VP/experiences to happen via product/service/attributes, etc.)

- Communicate it (ensure customers understand/believe it via Marketing, Sales, etc.)

Profitable Value? – If customers conclude that a VP is superior to the alternatives, it generates revenues; if the cost of delivering it is less than those revenues, then the business creates profit (or shareholder wealth) – thus, it is delivering profitable value.

* * * * *

4 areas where many businesses can improve on delivering profitable value:

- Avoid misunderstood, confused, and trivial definitions of ‘Value Proposition’

- Deliberately deliver the VP – rigorously define, link & manage each function to help Provide and/or Communicate the resulting experiences

- Think profitable value-delivery across the entire chain, not just the next link

- Discover new value-delivery insights by primarily exploring and analyzing what customers actually do, more than what they think and say they want

Now let’s consider each of these 4 areas in more detail:

- Avoid commonly misunderstood, confused or even trivialized definitions of a VP

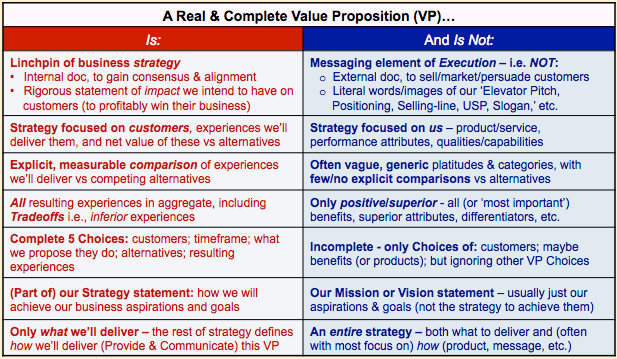

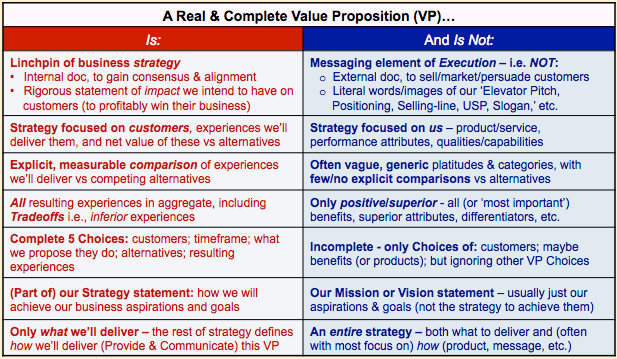

The table below summarizes some common misperceptions about Value Propositions, followed by some discussion of the first two.

Of these misperceptions, the first two are perhaps most fundamental, being either:

- Our message – an external document to directly communicate with customers, explaining why they should buy our offering; part of execution, not strategy

OR:

- Part of strategy, but focused primarily on us (not customers) – our products/services, performance-attributes, functional skills, qualities, etc., not customers’ experiences

It’s not your Elevator Speech – a VP is strategy, not execution – For much greater strategic clarity and cross-functional alignment, avoid the common misunderstanding that confuses and equates a VP with messaging. Execution, including messaging is of course important. A VP, as part of your strategy, should obviously drive execution, including messaging; but strategy and execution are not the same thing. If you only articulate a message, without the guiding framework of a strategy, you may get a (partial) execution – the communication element – of some unidentified strategy. But you forgot to develop and articulate the strategy! The execution might still work, but based more on luck than an insightful, fact-based understanding of customers and your market.

This common reduction in the meaning of a VP, to just messaging, not only confuses execution with strategy, but also only addresses one of the two fundamental elements of execution. That is, a VP must be not only Communicated, but also Provided – made to actually happen, such as via your products/services, etc. If customers buy into your messaging – the communication of your VP – but your business does not actually Provide that VP, customers might notice (at least eventually). Though some businesses actually attempt this approach – promising great things, but not making good – and may even get away with it for a limited time, a sustainable business obviously requires not only promising (Communicating) but actually Providing what’s promised.

And it’s not about us – focus VPs on customers, not our products, services, etc. – The other common misuse of the VP concept starts by treating it (rightly) as a strategic decision and internal document. But then (again missing the point) such a so-called VP is focused primarily on us, our internal functions and assets, rather than on the customer and resulting experiences we will deliver to them.

Here it’s helpful to recall the aphorism quoted by the great Marketing professor Ted Levitt, that people “don’t want quarter-inch drill bits, they want quarter-inch holes.” A real VP is focused on detailed description of the ‘hole’ – the resulting experiences due to using the drill bit – not on description of the drill bit. Of course, the drill bit is very important to delivering the VP, since the customer must use the drill bit, which must have the optimal features and performance attributes, to get the desired quarter-inch hole. But first, define and characterize the VP, in adequately detailed, measurable terms; then separately determine the drill-bit characteristics that will enable the desired hole.

- Deliberately deliver the VP – rigorously define, link and manage what each function must do to help Provide and/or Communicate the resulting experiences

It’s impossible to link Providing and Communicating value without a defined VP. However, even with a chosen VP, it is vital to explicitly link its resulting experiences, to the requirements for Providing it (e.g., product and service) and for Communicating it. Companies can improve market share and profitability by rigorously defining the VP(s) they aspire to deliver and then rigorously linking to the Providing and Communicating processes. Failure to make the right links leads to a good idea, not well implemented. (See more discussion of this Value Delivery framework here.)

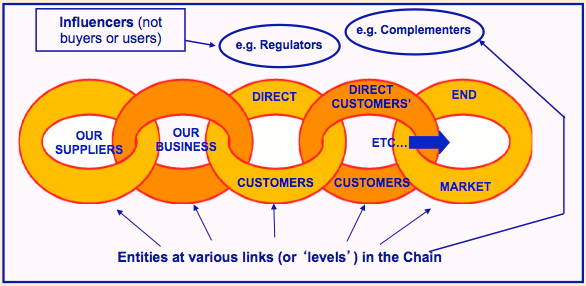

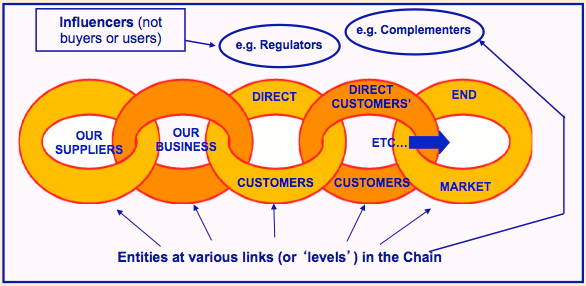

- Think value-delivery across the entire chain, not just the next link

Most businesses are in a value delivery chain – simple, or long and complex, e.g.:

Many companies survey their immediate, direct customer, asking them what they most value. Less often, they may ask what that customer thinks is wanted by players down the chain. They may rely for insight on that next customer, who may or may not be knowledgeable about others in the chain. There is often great value in exploring entities further down, to understand how each link in the chain can provide value to other links, including final customers, often with important implications for the manufacturer, among others. (See more discussion of Value Delivery Chains here.)

- For Value Proposition insights, explore and analyze what customers actually do, not what they think they want

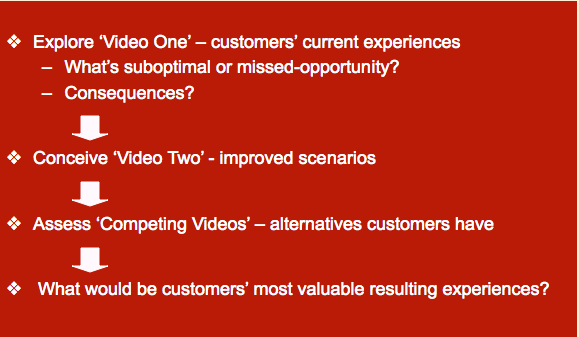

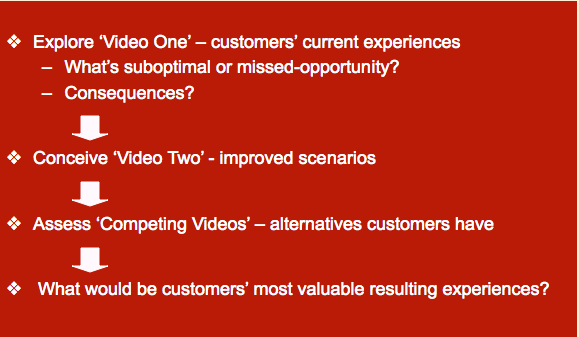

Businesses often conduct research, essentially asking customers, in various forms, to specify needs. A limitation of such research is that customers often filter their answers by what they believe are the supplier’s capabilities. We believe a better way is to deeply study what entities (at several links in the chain) actually do. First capture a virtual “Video One” documenting current experiences, including how an entity uses relevant products/services. Then create “Video Two,” an improved scenario enabled by potential changes by the business in benefits provided and/or price, but which somehow deliver more value to the entity than in Video One. Then construct a third virtual video capturing competing alternatives. Finally, extract a new, superior VP implied by this exploration. Results come much closer to a winning VP than asking customers what they want. (See here for more discussion of creatively exploring the market using this methodology.)